As access control systems become more advanced, the responsibilities placed on designers, installers and building operators have become equally complex. The release of Issue 4 of NCP 109, the NSI Code of Practice for the Design, Installation, Commissioning and Maintenance of Access Control Systems, reflects this reality and the current standards that support it.

Contents

- The Legal Foundation – Safety Comes First

- The Role of Harmonised Standards

- Fire-Safety Interfaces and BS 7273-4

- What issue 4 of NCP 109 adds – A Practical Framework

- Why the Industry Needs to Take This Seriously

- Putting It into Practice

- The NSI Perspective

- Frequently Asked Questions - FAQ

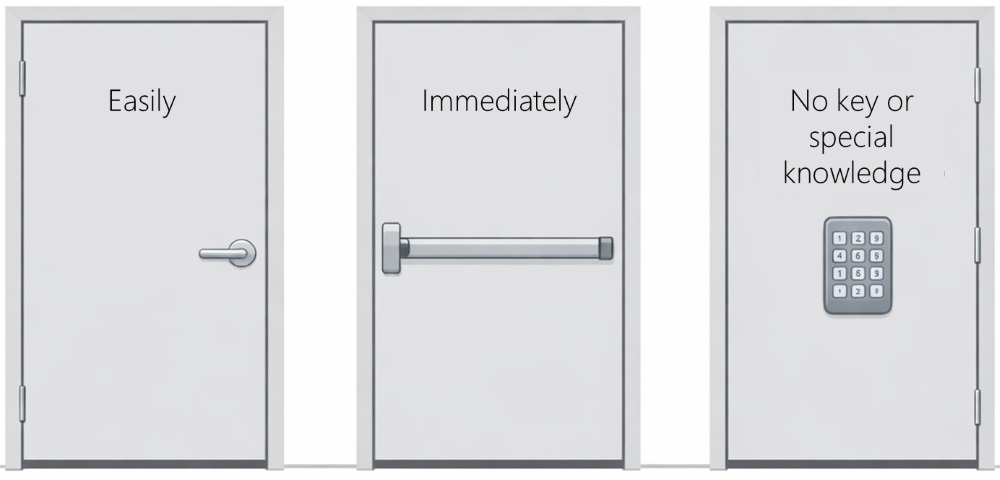

Building Standards across the UK

Although terminology differs across the four nations, all building standards require that doors on escape routes can be opened easily, immediately and without the use of a key or special knowledge.

England

Approved Document B (Fire Safety) and Approved Document M (Access) provide guidance on ensuring escape doors are readily openable. ADB advises that where more than 60 people may need to use an exit, a panic exit device to BS EN 1125 is recommended.

Wales

The Building Regulations (Wales) use their own set of Approved Documents, which give equivalent guidance to England on ensuring doors are readily openable for escape.

Scotland

The Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004 are supported by the Technical Handbooks (Domestic and Non-Domestic), which give guidance on escape-door operation and refer to BS EN 1125 and BS EN 179 as suitable panic/emergency exit devices.

Northern Ireland

The Building Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2012, supported by Technical Booklet E: Fire Safety, set the functional requirement that exits and escape routes must remain available and easy to use. Technical Booklet E references BS EN 1125 among its cited publications.

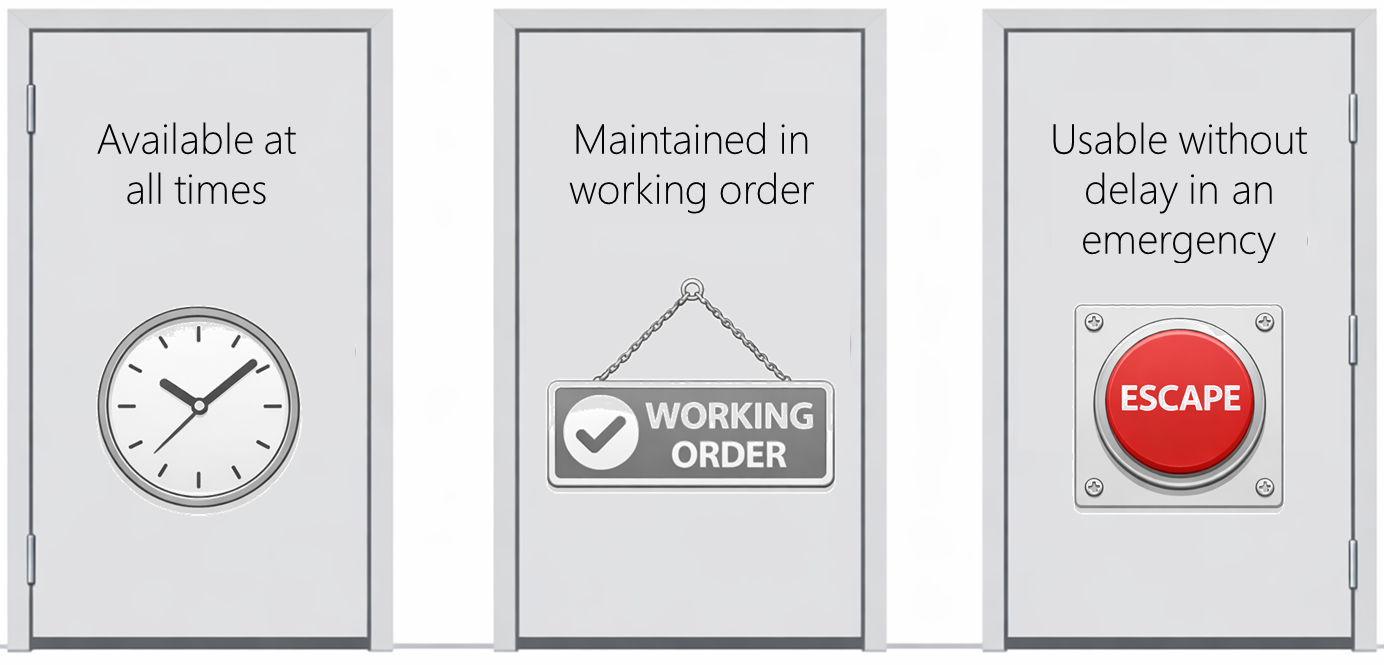

Fire-Safety Legislation

Across the UK, fire-safety law places a clear and consistent duty on the Responsible Person or Duty holder to ensure that escape routes and exits are:

This duty arises under:

England & Wales

Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005

Scotland

Fire (Scotland) Act 2005 and Fire Safety (Scotland) Regulations 2006

Northern Ireland

Fire and Rescue Services (Northern Ireland) Order 2006 and associated regulations

The Bottom Line

Across all four nations, the message is the same: whatever access-control system is installed, people must always be able to escape easily, immediately and without confusion or delay.

Whatever access-control system is installed, people must always be able to escape easily, immediately and without confusion or delay

The Role of Harmonised Standards

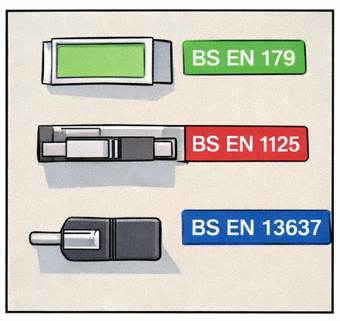

Three key British/European standards describe how compliant escape hardware should perform:

| Standard | Typical Use | Description |

|---|---|---|

| BS EN 179 | Staff or restricted areas | A lever handle or push pad operated by trained users familiar with escape routes. |

| BS EN 1125 | Public areas | A horizontal bar that allows intuitive, single-hand operation even in panic situations. |

| BS EN 13637 | Electrically controlled exit systems | Combines electronic control and safe egress within a single tested system. |

BS EN 179 and BS EN 1125 have been in use since the 1990s and were adopted widely in the early 2000s as the recognised standards for emergency and panic exit hardware. BS EN 13637 was introduced in 2015 to address the growing need for controlled or supervised egress using electronic systems.

All three standards are harmonised under the Construction Products Regulation (EU 305/2011) and have been since 2004, which remains retained in UK law. Products tested to these standards must carry a CE or UKCA mark and be supported by a Declaration of Performance that details the scope and levels of compliance/conformance.

Although these standards have existed for many years, they are being discussed more frequently now because electronic locking is far more common than when many buildings were originally designed. As installers retrofit access control to escape doors, the interaction between electronic locks, Building Regulations, fire strategies and EN escape hardware has become much more significant. NCP 109.4 brings these long-standing requirements into focus and asks that they now be considered, helping ensure that escape performance and product certification are not unintentionally compromised.

If an existing escape door is to become electronically controlled, the locking hardware should be certified to the same appropriate harmonised standard (BS EN 179, BS EN 1125 or BS EN 13637) to maintain both product compliance and life-safety performance.

Fire-Safety Interfaces and BS 7273-4

BS 7273-4 provides guidance on how electrically powered locking and door-release systems should interface with fire detection and alarm systems. It sets out how such doors should unlock or release on fire alarm activation, loss of power, or via an appropriate override device, in accordance with the building’s fire and escape strategy.

BS 7273-4 is most commonly applied where a door relies on electrically powered locking to permit escape, such as magnetic locks, electrically held locks, or other electrically controlled devices. In these situations, it is the recognised way of demonstrating that the fire-safety interface meets the requirements of the Building Regulations and the Fire Safety Order. Equivalent statutory duties apply in Scotland (the Building (Scotland) Regulations and the Fire (Scotland) Act 2005) and Northern Ireland (the Building Regulations (Northern Ireland) and the Fire and Rescue Services (Northern Ireland) Order 2006), all of which require that escape doors are readily openable and release immediately in an emergency.

However, BS 7273-4 does not determine whether a locking solution is suitable for use on an escape door. Where a door is already fitted, or is intended to be fitted,with compliant mechanical escape hardware tested to BS EN 179 or BS EN 1125, escape is achieved independently of power or fire alarm operation. In those cases, BS 7273-4 is not relied upon to provide the means of escape and should not be used as a substitute for compliant escape hardware, as it could introduce a second action.

Getting in

Mechanical escape devices, such as those tested to BS EN 179 or BS EN 1125, already provide safe, single-action mechanical egress and do not rely on BS 7273-4 for handling the release, even when they are also operated electronically.

They work just like an ordinary handle or panic bar, and they still let you out even if the power goes off. A simple example is a hotel room door: you use your keycard to get into the bedroom corridor or your room, but when you want to leave, you just use the handle and walk out (a single simple action). The electronic system only controls who can enter; the handle always works normally from the inside, so you can get out quickly and safely at any time. This is why you rarely see maglocks in hotel bedroom corridors; the escape route always has to remain simple, single-action and intuitive.Getting out

When electronic secure egress (getting out) control is required on a door that would normally be fitted with or already has fitted a BS EN 179 or BS EN 1125 device, the system should comply with BS EN 13637, which defines electrically controlled exit systems and is referenced within BS 7273-4.

Electronic control may be justified where additional functions are necessary, such as:

In all cases, if electronic control is added, the escape function must remain single-action, and the system must interface correctly with the fire-alarm system in accordance with BS 7273-4

Why the Industry Needs to Take This Seriously

Modern access control has outpaced many older building designs. Doors installed decades ago are often retrofitted with electronic locks or readers without checking how this affects the ability to escape. That can leave the Responsible Person or Duty holder unknowingly non-compliant with fire safety legislation or Building Regulations.

NCP 109 Issue 4 addresses this by requiring a proper, site-specific assessment.

It doesn’t dictate which lock to use. It simply asks installers to think, to understand the risks, and to record the reasoning behind every design decision, as well as listen and understand the fire and escape risk strategy from the client.

Putting It into Practice

Good practice under NCP 109.4 begins with a thorough understanding of each door’s role and certification.

Survey each door carefully.

Identify whether it forms part of an escape route, a fire compartment line or a secure zone. Record how it is used, who uses it, and what function it was originally designed and certified for. Any new locking or access-control solution must maintain that intended design performance, whether fire resistance, smoke control, acoustic rating, or escape classification and must not compromise its certification or safe operation.

Check CE or UKCA marks and Declarations of Performance.

Confirm that components used on the door, including electronic hardware, are tested and certified to the relevant BS EN standard and compatible with the door manufacturer’s certification.

Apply BS EN 179, 1125 or 13637 as appropriate.

Match the hardware standard to the door’s intended use and occupancy type, ensuring single-action egress and correct interface with access-control equipment.

Understand when electrically powered locking, including magnetic locks, may be appropriate.

Approved Document B does not prohibit the use of magnetic locking devices, and neither does NCP 109. Their suitability depends on the door’s role within the escape strategy. Where a door forms part of an escape route, it must be readily openable without a key or specialist knowledge and must fail safe on fire alarm activation, loss of power, or via an appropriate override device, in accordance with BS 7273-4 and the site-specific fire strategy. However, where compliant mechanical escape hardware (such as BS EN 179 or BS EN 1125 devices) is already fitted, retrofitting a magnetic lock that introduces more than one action to escape may compromise compliance and life safety. These distinctions must be understood and documented at the design stage.

Apply BS 7273-4 for any door that is electrically locked and linked to a fire alarm as appropriate.

Ensure automatic release on alarm or power failure and confirm that the wiring and control meet the category required by the fire strategy.

Protect the integrity and certification of all fire-rated door sets.

Avoid cutting, drilling, or modifying any component of the door set beyond the manufacturer’s tested design, and keep documentation or approval evidence for all work carried out.

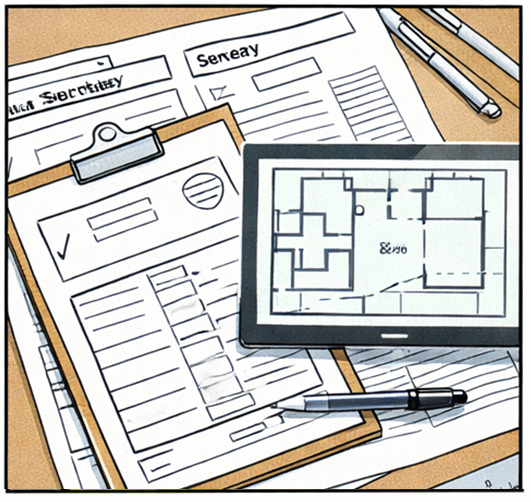

Maintain clear records.

Keep copies of all risk assessments, design proposals, installation details and test results.

These records demonstrate compliance and show that the Responsible Person has exercised due diligence providing defensible proof of meeting their legal obligations under the Fire Safety Order and Building Regulat

The NSI Perspective

NCP 109 Issue 4 is not about adding bureaucracy or making life difficult for installers. Its purpose is to provide a framework to help them make confident, well-informed decisions, protect themselves, and deliver safer outcomes for their clients. By setting out how existing laws, regulations, and standards fit together, the Code provides a clear route to compliance and helps installers avoid the uncertainty that often surrounds complex escape and access-control situations.

It gives companies/specifiers and interested parties a framework they can rely on, ensuring that the systems our certified companies design and install are both secure and legally defensible.

NCP 109 is there to support the industry, not restrict it.

It helps installers find the right solutions, demonstrate competence, and show clients that they take safety and compliance seriously.

But yes, it may also prevent the wrong or cheapest solution from being fitted when that choice could compromise safety, compliance, or integrity.

In that respect, the Code protects everyone involved, the installer, the client, and the building’s occupants.

Working with an NSI Certified company gives purchasers, building owners and duty-holders confidence that their systems are designed, installed, and maintained by professionals who are independently audited for technical competence, documentation, and adherence to recognised codes of practice.

Frequently Asked Questions

Disclaimer

The information provided in this document reflects our understanding of current standards and best practice at the time of publication. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, guidance and legislation may change, and interpretations can vary. This document is not intended to constitute legal advice or serve as a definitive installation guide.

As an independent third-party certification body, we cannot provide consultancy advice or recommend specific solutions for individual applications.

Where there is any uncertainty regarding the type of locks or systems to be used, readers should seek clarification from Building Control Officers, qualified fire safety consultants, or obtain independent legal advice to ensure compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.

We accept no responsibility or liability for any loss, damage, or consequences arising from reliance on the information contained in this document.